Politics

/

November 13, 2024

The difference between what the answer should be—and what it will be—tells you almost everything you need to know about today’s Democratic Party.

US Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor during the celebration of Women’s Day at the Constitutional Court on March 4, 2024, in Madrid, Spain.

(Eduardo Parra / Europa Press via Getty Images)

Should Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor retire before January 20 so Biden can replace her before he leaves office? It’s a question that’s been on the mind of liberals since it became obvious that Donald Trump and his ruling junta had won control of all three branches of government. The Republicans will control the White House, the House, and the Senate. They already control the Supreme Court. Potentially ceding yet another seat to the Republicans feels like the last thing Democrats should do in the current environment.

In reality, there is little practical difference between the current 6–3 Republican supermajority on the court and a potential 7–2 Republican supermajority. Justices like John Roberts, alleged attempted rapist Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett side with the liberal minority only rarely, and even then, they often move as a block. It doesn’t actually matter in the near term if liberals dissent from all the important cases with two votes or three votes—they’re still going to lose every issue they care about.

And yet, Sotomayor should certainly retire now. If Democrats ever hope to retake the court through the normal course of appointments and retirements (which isn’t projected to happen until at least 2045, assuming Democrats are still allowed to win elections and appoint justices), then having one less conservative appointment to overcome is valuable. A young liberal justice appointed now might live long enough to see Democratic control of the Supreme Court again; Sotomayor, alas, likely will not. She is 70 years old. She’s lived with Type-1 diabetes most of her life. And while reports vary widely about the current state of her health, Democrats have rolled the dice with aging liberal justices in the past—and lost.

Donald Trump’s election means that liberal justices on the Supreme Court will have to live for another four years, at least. Even if you think that Trump’s successor (if he has a successor) can be beaten in 2028, Daniel Block explains that Republicans are poised to have long-term control of the US Senate. This means that it’s likelier than not that liberal justices will actually need to live for another eight years, or more, before there will be a reasonable chance to replace them with a Democratic appointee. As the oldest of the three liberal justices, Sotomayor should retire now, and Biden and the Democrats should ram through a replacement before they leave office, and that replacement should essentially be a 20-year-old recent law graduate who can be counted on to outlive the coming darkness of one-party Republican rule.

Of course, that’s not going to happen. Sotomayor will not retire, and Democrats will not push through a replacement. The reasons for this are simple: Democrats continue to refuse to use their power maximally when it comes to the federal judiciary. The party is, in a word, “weak,” and lacks the strength of will to do what is necessary. Sotomayor will be allowed to continue in her post, leaving all of us to hope she outlives a Trump administration or a Vance administration or a Senate controlled by Republicans.

If that does not happen, liberals will bemoan the fact that she did not retire when she “had the chance,” much like they continue to criticize the (long dead) Ruth Bader Ginsburg for not retiring during the Obama administration. Now is that “chance,” but we will be forced to watch as Democrats blow it in real time, and then live to see those same Democrats regret it later.

Current Issue

The problem starts at the top, which in this case, is Sotomayor herself. Her people have been talking to The Wall Street Journal and, guess what, she doesn’t want to retire. A consistent problem with Supreme Court justices is that they really like being Supreme Court justices and put their personal preferences over the good of the country. These people, imbued with power for life, come to think that they—not their votes—are indispensable.

I love Sotomayor. I think she’s been one of the best Supreme Court justices in history. She is who other people think Ruth Bader Ginsburg was. But there are thousands and thousands of people who could do what she does (being a Supreme Court justice is not nearly as hard as these people would have you believe), vote like she votes, and dissent like she dissents. She should realize that her mission is more important than her career. She should leave now so the next Sotomayor can carry on. But Supreme Court justices don’t really think like that. Indeed, in this moment, Sotomayor is acting… just like everybody else.

But it would be wrong to be too harsh on Sotomayor, because she is also very smart and can read the tea leaves as well as anybody. What those leaves suggest is that the craven Democratic Party, as currently constituted, would probably be unable to replace her during the lame-duck session even if she retired. Democrats will officially lose control of the Senate in January, but the reality is that they lost control long ago. Replacing Sotomayor would require the full participation of Senate Democrats, and that’s something this ailing and unserious party cannot accomplish. Soon-to-be ex-Senator Joe Manchin will not vote for a Sotomayor replacement in the lame-duck session, and who knows where soon-to-be ex-Senator Kyrsten Sinema is these days.

And it’s not just these two longtime traitors who are likely to scuttle any Democratic attempt to wield power. We know this because, separate and apart from the Sotomayor question, there are currently 41 federal judicial vacancies that Biden and the Democrats have not filled. And that number doesn’t include a number of federal judges, at least three on the circuit court, who would like to take senior status now, pending the confirmation of a replacement Biden has already named but the Senate hasn’t confirmed.

All of these federal vacancies can be filled by Trump and his Republican Senate once they take office, and yet the Democrats are unlikely to fill them all before they leave. For those playing along at home, Trump and Mitch McConnell confirmed 13 federal judges in the lame-duck session after Trump lost the last election in 2020—including Florida district judge Aileen Cannon. (And I’m not even counting the confirmation of Supreme Court Justice Amy Coney Barrett in the figure, even though she was confirmed by Republicans after the election to replace them had already started.)

Outgoing Senate Judiciary chairman Dick Durbin is the primary culprit for this shocking malpractice. He has not moved as aggressively as he should have to fill district-court seats in Republican-controlled regions. But the larger Democratic caucus has also been weak on appointing judges Republicans don’t like. It’s not just Manchin and Sinema—check out this nugget, reported in Salon: “The recently re-elected senator from Nevada, Jacky Rosen, said before the election that she wouldn’t vote for the nominee for the Third Circuit Court, Adeel Mangi. Her colleague from Nevada, Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto, said the same thing ahead of the election.” Mangi is Muslim, by the way, but the senators say their objection to confirming him stem from “concerns from law enforcement,” because Mangi has worked with criminal justice reform groups opposed to mass incarceration. This party is beyond lost.

The inability of Senate Democrats to move aggressively on court appointments is unforgivable. When I point this out, progressives rightly get on a high horse about the fecklessness of “establishment Democrats,” but when it comes to action, many progressives are hardly better than the regular party poo-bahs. On Meet the Press this Sunday, Senator Bernie Sanders said that talk about replacing Sotomayor during the lame-duck session was not “sensible.”

Again, I get it. Bernie’s not wrong, at least if I’m interpreting him correctly. It’s not “sensible” for Sotomayor to step down if Sanders knows, as I know, that there are not the votes in the Senate to replace her. But I can’t help noticing that while progressives, like Sanders, are blasting the Democratic Party for its long-term inability to connect with working-class Americans, they consistently miss that the Supreme Court does not allow progressive policies to happen, even when Democrats try. Popular policies like student debt relief were scuttled by the Supreme Court—and even if Harris had won, the Republican court would have been a conservative bulwark against abortion rights, environmental justice, or the restoration of voting rights.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Ceding control of the third branch of government to a deeply unpopular, hyper-conservative supermajority for a generation is the thing that limits the scope of the Democrats’ response to problems. And it warps our politics. We have to fight about things like gay rights and transgender rights in the political sphere because we have a Supreme Court that will not apply the equal protection of laws to the LGBTQ community. We have to fight rearguard actions to protect the basic dignity of immigrants because the Supreme Court will not apply widely accepted human rights standards to immigrants. Economic progressives always want to focus on the “kitchen-table” economic issues that allegedly motivate Trump’s racist band of followers, but we can’t solely focus on such “real world” concerns as the price of eggs when the Supreme Court allows minority communities to be repeatedly violated by the mob of cis-hetero white folks who also like cheap eggs. If we had a progressive Supreme Court, our elections wouldn’t be a life-or-death proposition for vulnerable communities.

Progressives don’t really want to have that conversation right now, but replacing Sotomayor in the lame-duck session would be a small progressive win in the face of overwhelming defeat. Filling the 41 judicial vacancies right now would be a progressive win. Republicans have always understood that control of the courts is the thing that protects their agenda even in the face of electoral losses. Democrats never learn the lesson, and progressives never push them to do so.

I said, repeatedly, that the first thing Biden should have done when he came to power (with Democrats in control of the House and Senate) in 2021 was reform the courts. I said repeatedly that reforming the courts was the way for Democrats not only to secure their agenda but to make sure we had the kind of voting access necessary to secure future Democratic electoral victories.

Instead, we got a commission on Supreme Court reform—which failed even to recommend meaningful reform—and rolled into another election with voting rights far more restricted than they were during the previous one. And yet Democrats now wonder where millions of votes went and sound like lunatic conspiracy theorists when they do. Turnout was lower in 2024 at least in part because voting was harder than it was in 2020. Voting was harder because the Supreme Court made it that way and allowed individual states to make it that way. The failure of the Democratic Party to secure voting rights through aggressive court reform was always going to be the source of its downfall.

In any event, it doesn’t matter now. Republicans won, and they will likely control the federal judiciary, including the Supreme Court, for the rest of my natural life. I feel like it borders on pointless to even ask the Democrats to swap out one aging minority justice for a younger one now, because Democrats are too far gone to listen to reason. Sotomayor is not going to retire. Progressives are not going to demand that she retire, and Democrats are not going to hold together enough to replace her. Democrats are not going to fill the 41 lower-court vacancies either. Democrats are going to lose, continue losing, and then blame transgender teenagers for their losses.

We could have addressed this in 2021. Now, we will enjoy the consequences of our inaction.

We cannot back down

We now confront a second Trump presidency.

There’s not a moment to lose. We must harness our fears, our grief, and yes, our anger, to resist the dangerous policies Donald Trump will unleash on our country. We rededicate ourselves to our role as journalists and writers of principle and conscience.

Today, we also steel ourselves for the fight ahead. It will demand a fearless spirit, an informed mind, wise analysis, and humane resistance. We face the enactment of Project 2025, a far-right supreme court, political authoritarianism, increasing inequality and record homelessness, a looming climate crisis, and conflicts abroad. The Nation will expose and propose, nurture investigative reporting, and stand together as a community to keep hope and possibility alive. The Nation’s work will continue—as it has in good and not-so-good times—to develop alternative ideas and visions, to deepen our mission of truth-telling and deep reporting, and to further solidarity in a nation divided.

Armed with a remarkable 160 years of bold, independent journalism, our mandate today remains the same as when abolitionists first founded The Nation—to uphold the principles of democracy and freedom, serve as a beacon through the darkest days of resistance, and to envision and struggle for a brighter future.

The day is dark, the forces arrayed are tenacious, but as the late Nation editorial board member Toni Morrison wrote “No! This is precisely the time when artists go to work. There is no time for despair, no place for self-pity, no need for silence, no room for fear. We speak, we write, we do language. That is how civilizations heal.”

I urge you to stand with The Nation and donate today.

Onwards,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editorial Director and Publisher, The Nation

More from The Nation

California and the other powerful Democrat-led states will be the first line of defense under Trump’s new administration.

Sasha Abramsky

The once and future president tried to oust Thune from the Senate in 2022. Thune won another term. Now, he’s the Senate majority leader.

John Nichols

The party continues to operate in an overcredentialied fever dream in the face of an America becoming ever more red in tooth and claw

John Ganz

A conversation with former Biden primary challenger Representative Phillips on the election, his run for presidency, and the future of the party.

StudentNation

/

Owen Dahlkamp

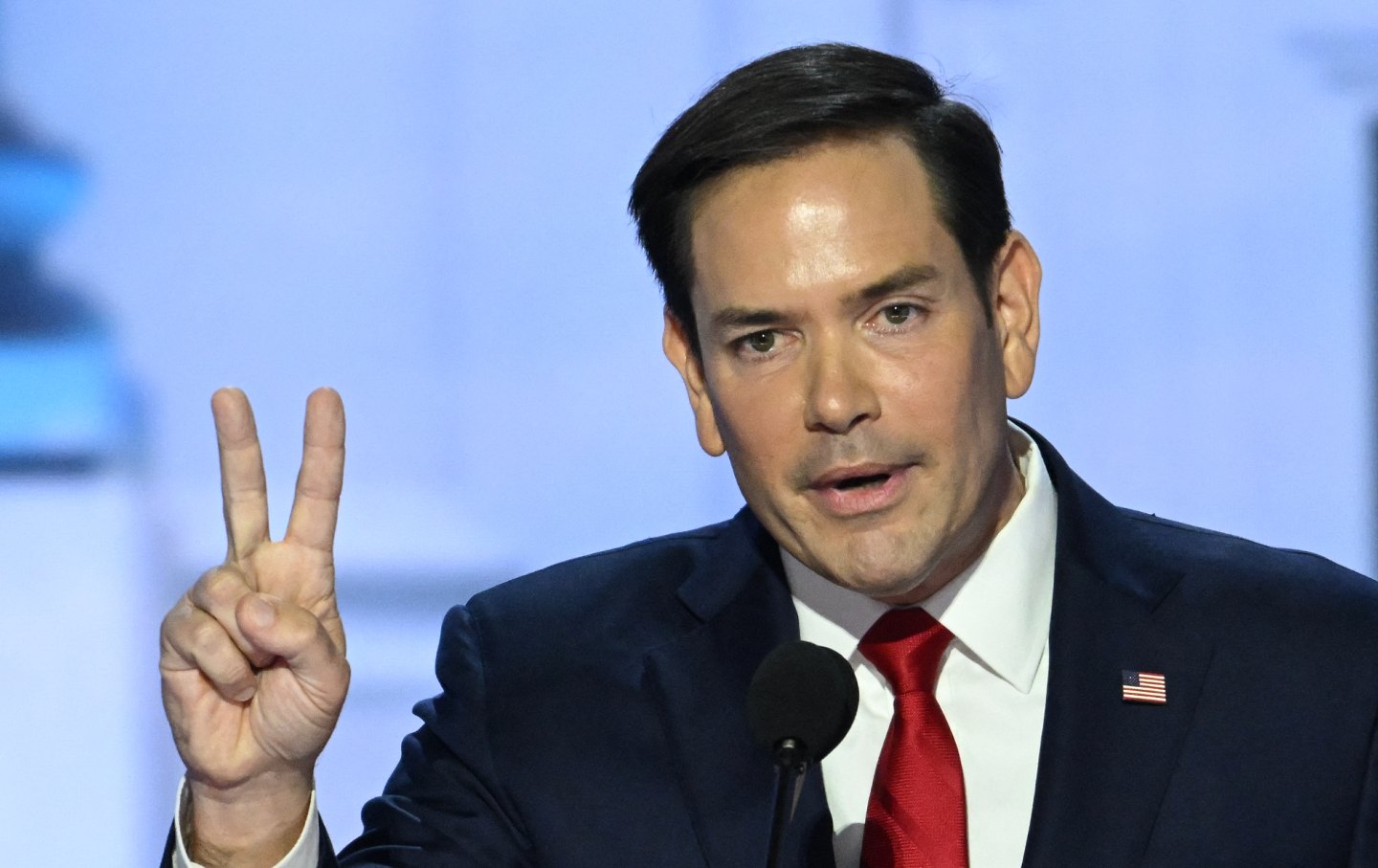

Democrats are falling over themselves to hail Marco Rubio’s nomination as secretary of state.

Aída Chávez